Separating quality management and risk management may look neat on paper, but it creates a serious gap in practice. The two systems depend on each other. In short: without risk management, quality management does not work. In medtech this matters more than anywhere else, because devices and SaMD touch life and health. High quality and low residual risk are not separate goals here, they describe the same outcome from two angles.

This article outlines how QMS and risk management reinforce each other, and how manufacturers can bring risk management requirements into an existing QMS so that risk stops living in a file and starts steering decisions.

A QMS and risk management form the backbone of safe and effective medical devices. ISO 13485 provides the QMS framework, while ISO 14971 lays out the internationally accepted risk management process.

ISO 14971 frames risk management as a lifecycle activity: hazards are identified, risks are analysed and evaluated, controls are implemented, and then the whole system keeps monitoring whether those controls still work. This is exactly where ISO 13485 becomes practical. It turns “do risk management” into controlled processes: planning, responsibilities, records, traceability, and feedback loops. That is also why many regulatory expectations—EU MDR/IVDR as well as FDA requirements—are easier to meet when risk thinking sits inside the QMS rather than beside it.

One practical bridge between “risk-based” and daily execution is the device’s risk class. In the EU for example, risk class is typically derived from the intended use, invasiveness, duration of use, and the potential severity of harm. A consistent, written rationale for the classification matters, because that classification directly influences the depth of evidence expected: technical documentation, clinical evaluation, and the overall verification and validation workload.

When integration works, risk-based decisions become the default in product development, manufacturing, supplier management, and post-market surveillance. The QMS stops acting like a compliance shell and starts behaving like a learning system. Integration typically delivers four concrete advantages: safer and more effective devices; smoother compliance with strict regimes (MDR, FDA); higher efficiency through standardised workflows and traceability; and a quality culture that consistently prioritises patient safety.

Key standards and regulations

A QMS that embeds risk management is not a “nice to have”. Key jurisdictions effectively require it.

The relationship between ISO 13485 and ISO 14971 becomes clearer when viewed as “wiring”, not as two parallel standards.

That integration shows up through a small set of core activities that a functioning QMS must support, in one form or another: identify hazards, analyse risk (severity and probability), implement controls (design measures, protective features, information for safety), evaluate residual risk, and monitor whether the overall risk picture changes over time. The list matters less than the loop. “Proactive” means the loop runs continuously, especially when new data arrives.

Risk management should run as a principle through the entire QMS, not as a single isolated process. Still, several QMS areas carry particularly high “risk weight”. These are the places where integration should be visible and auditable.

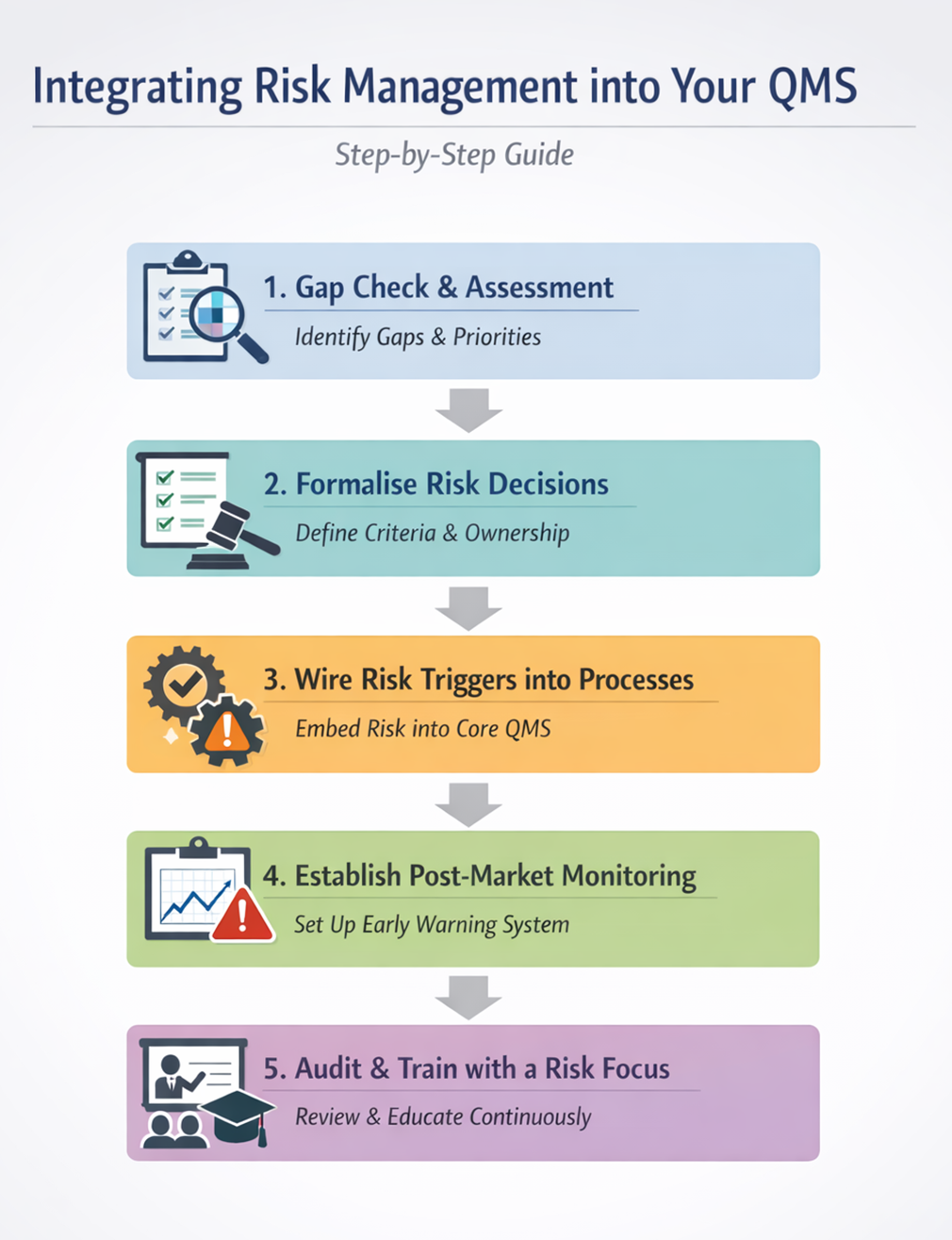

Many manufacturers already run a QMS and hold a risk file. The real work lies in making risk drive everyday decisions.

A practical start is an RM integration assessment as a focused workshop (often one to two days). The workshop should map where risk is merely documented versus where it genuinely influences decisions. It should also identify which QMS processes have mandatory triggers for risk review, and which do not.

The baseline references typically include ISO 13485:2016 (risk-based process control; product realisation/planning; design and development; purchasing; production; CAPA/feedback/complaints; internal audits; management review) and ISO 14971 (risk process plus post-production information/monitoring).

Findings from the gap check only matter if governance turns them into practice. Risk decisions need clear ownership: who defines and changes acceptability criteria, who approves residual risk, and when escalation to management becomes mandatory. Many organisations achieve this without creating new bureaucracy by adding a fixed “risk” agenda item to existing forums such as design reviews, change control boards, or management review. Others create a small risk review board with defined decision rights.

A simple but powerful record here is a standardised Risk Impact Assessment form that becomes a normal QMS record, used consistently, not only during audits.

The goal is straightforward: every critical process has defined inputs from risk management and defined outputs back into risk management.

In design and development (ISO 13485: 7.3; FDA 820.30), risk controls should map to design inputs, and verification/validation should explicitly cover those controls through traceability. In purchasing (ISO 13485: 7.4; FDA820.50), supplier criticality should drive qualification and oversight, including change notification for critical suppliers. In production and process controls (ISO 13485: 7.5), validation and monitoring should focus on risk drivers, with clear revalidation triggers such as process changes, drift, or out-of-spec trends. In change control, a risk impact assessment should become mandatory for relevant changes; when the risk profile shifts, the system should trigger additional V&V (verification/ validation) and updates to the RM file and, where needed, labelling/IFU.

For CAPA, complaints, and feedback (ISO 13485: 8.2/8.5; FDA 820.198 and820.100), triage and prioritisation should follow risk (severity, frequency,detectability, potential harm), and RM file updates should be a defined output.

Proactivity lives or dies in post-market work. Hard rules beat gut feel: trend thresholds for complaint rates, recurring failure modes, service data, and nonconformities help detect signals early. Clear capture criteria also matter, so the system consistently records what must be recorded—complaints, incidents, reportable events, and relevant trends—before they get debated case by case.

“Weak signal” rules clarify when a signal triggers investigation/CAPA versus when it triggers a targeted risk review. ISO 14971 monitoring becomes practical when data sources, review frequency, and responsible roles are fixed, and when reassessment produces a consistent record (for example, a quarterly or event-driven risk reassessment report). For higher-class products, this should sit inside a structured post-market surveillance plan and, where appropriate, include planned collection of clinical or performance data rather than relying solely on passive feedback.

Internal audits (ISO 13485: 8.2.4) should follow risk-based planning: critical processes should face deeper and more frequent audits. A useful audit test is not “does a risk document exist?” but “does risk truly influence decisions?” Management review (ISO 13485: 5.6) then acts as risk steering: top risks, new hazards, trend signals, CAPA effectiveness, and supplier risks should lead to concrete decisions on resources, priorities, acceptability criteria, and process adjustments, with owners and deadlines.

Integration also depends on people, and ISO 13485 explicitly requires organisations to ensure competence through training. Risk-relevant roles, typically design and verification teams, production and inspection, customer support, complaint handling, and vigilance, need defined competence requirements (training, experience, product knowledge, and process understanding). Training should build risk perspective, and its effectiveness should be checked for critical activities (for example through observation, testing, or a four-eyes release).

ISO 13485 and ISO 14971 do not ask for two separate systems. They push toward one integrated way of working: risk management that actively drives QMS decisions across the lifecycle. A proactive QMS recognises risk early, turns it into controls, and then checks those controls through real data: complaints, trends, CAPA effectiveness, supplier performance, and production signals. For medtech manufacturers, that integration strengthens safety, improves compliance readiness, and keeps quality efforts focused where they matter most.

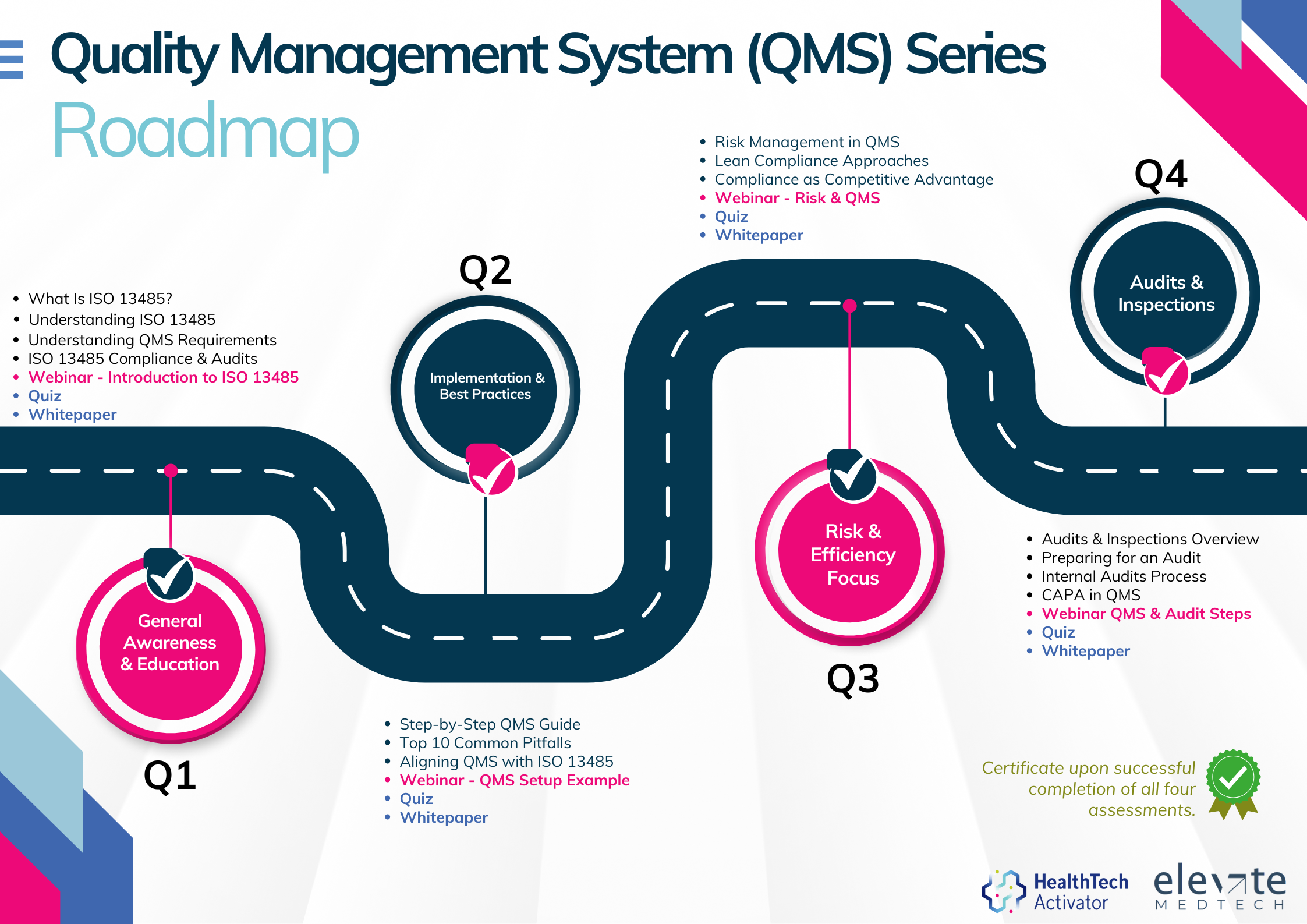

Meeting the requirements of ISO 13485 is one thing, putting them into practice is another. That’s why this article is part of a broader series developed for New Zealand’s HealthTech sector, aimed at helping teams turn regulatory expectations into working systems.

Over 12 months, this series explores ISO 13485 in four parts: from first steps and system setup to risk management and audit readiness. Each quarter combines practical content with interactive workshops to support implementation in real-world settings.