Anyone who tries to put an ISO 13485 QMS into real practice runs into the same wall, sooner or later: the mind-bending complexity of legal and quasi-legal texts. Requirements hide behind dense clauses, cross-references multiply, and suddenly a “simple” QMS touches risk management under ISO 14971, plus national rules that refuse to sit still. There is a reason law fills entire degree programmes.

So, what helps when the rules feel bigger than the business?

This article shows how organisations can strip ISO 13485 down to its core and implement it with a lean, risk-oriented approach, without cutting corners, and without drowning in paperwork.

ISO 13485 itself, and especially its day-to-day implementation, has a reputation: complex, heavy, headache-inducing. That complexity rarely comes from a single source. It builds up from several forces at once.

ISO 13485 expects strong control and traceability. In practice, the hard part is not “having documents”, but keeping full, consistent records for many processes at the same time. Without a clear strategy, documentation turns into a second job, or worse, a chaotic archive that nobody trusts.

Unlike broader quality standards such as ISO 9001, ISO 13485 leans heavily on risk management in line with ISO 14971. That means the QMS cannot stop at defining processes. It must also force a disciplined habit: identify risks that could affect patients and users, assess them, and reduce them in a systematic way.

Medical device requirements come largely from national legislation. And legislation changes. The consequence is uncomfortable but real: a QMS needs ongoing adjustment, sometimes across several markets at once.

Most organisations already have working routines. Bringing them into ISO 13485 often means changing habits, roles, approval paths, and documentation culture. That can feel harder than building processes from scratch, because old workflows come with history.

Trying to hold all of this in the head at once often leads to overload. Overload burns resources, and ironically it can damage quality: teams start to document for the sake of documenting, audits become theatre, CAPAs pile up, and the system slows down the very learning it should enable.

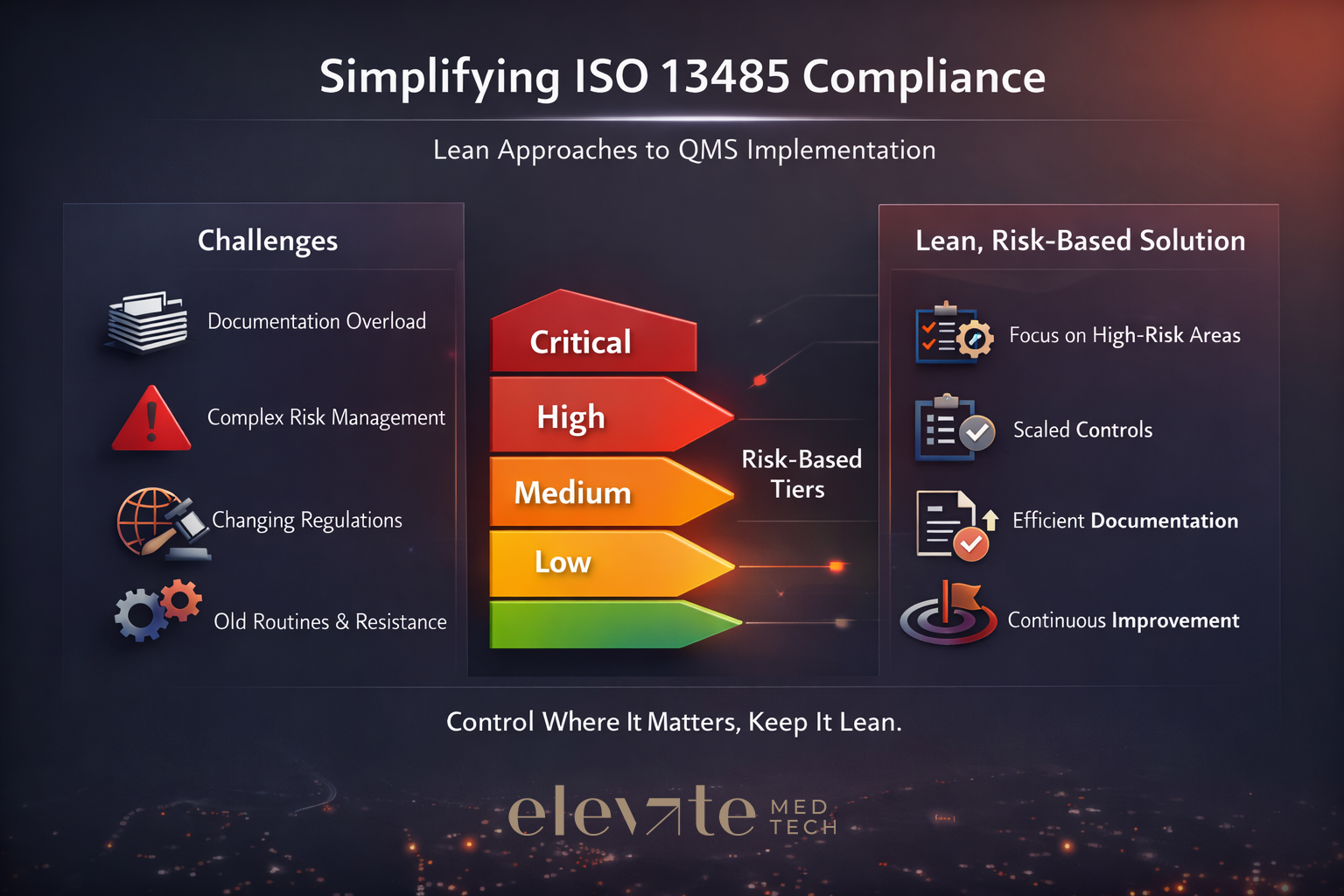

That is why reducing complexity matters. The key is doing it without slipping below the standard’s requirements. The practical answer is a lean system that uses risk as the organiser.

A lean ISO 13485 QMS does one thing on purpose: it puts the most effort, control, and documentation where risk is highest, and keeps everything else deliberately lightweight. For startups and for large corporates, the principle stays the same. Risk becomes the primary filter for what becomes formal, what gets reviewed often, and what can stay simple.

A lean, risk-based system typically behaves like this:

Lean does not mean “less compliant”. It means “more intentional”.

First, risk management under ISO 14971 needs to connect to the QMS processes that shape the device across its life cycle: design, purchasing, production, post-market surveillance (PMS), complaints, change control.

Second, two types of risk deserve a clean separation, because they get mixed up all the time:

Third, controls should match risk. The “weight” of the system—SOP depth, approvals, record detail, review frequency—should rise with risk and relax when risk is low.

A simple risk rating (often severity × occurrence) can then drive decisions that normally cause endless debate:

The practical goal is not to create the perfect model. The goal is consistency: the same logic, used everywhere, so the organisation can explain, and defend, why one process is tightly controlled and another is intentionally lighter.

A small set of tiers is enough. Three to four levels typically do the job (for example: Low / Medium / High / Critical). The crucial part is a short, written definition that links each tier to impact on:

A workable example definition for High might read like this: a process failure could reasonably lead to patient harm or major regulatory action (typical candidates: design controls, sterilisation, complaint handling).

A simple table beats an overengineered model. List ISO 13485 processes—design, purchasing, production, PMS, document control, training, and so on—and add, per process:

A practical shortcut keeps effort where it belongs: do a light FMEA-style exercise only for the highest-impact processes; keep low-risk processes to a short narrative or a few bullets that capture the obvious failure modes.

This step removes day-to-day friction. Instead of arguing about every SOP, set a generic matrix that says: if a process sits in this tier, it gets this level of control.

For each tier, define things like:

An example rule works well because it reads like common sense: high-risk processes require a documented procedure, training records, defined KPIs, and at least annual internal audit; low-risk processes may only need a work instruction and ad-hoc monitoring.

Make risk visible in the documents themselves. A mandatory field—dropdown or checkbox—on each SOP or form (“Risk impact: Low / Medium / High / Critical”) can change behaviour.

Then configure document control so the risk flag drives workflow:

A concrete example shows the difference immediately: a Complaint Handling SOP tagged High should trigger QA review, training updates, and perhaps a quick effectiveness check when it changes. An Internal Meeting Scheduling work instruction tagged Low should not need that overhead.

5) Put effort where the risk sits

Apply risk-based rules to the areas that matter most:

Design inputs, risk analysis (ISO 14971), verification, and validation depth should follow the device and software risk class. A Class IIb implantable will demand more formal reviews, traceability, and validation than a low-risk accessory.

Internal audits and CAPA

Audit frequency and sample size should follow process risk and recent performance. CAPA should stay reserved for high-risk or systemic issues. Isolated, low-risk nonconformities can often be handled with a quick correction and a short record.

No system works if leadership only nods along and then disappears back into day-to-day firefighting. A lean, risk-based approach stays lean only when it gets made official from the top, as a clear direction: this is how documentation works here, and this is how control scales with risk.

A short policy statement can do most of the heavy lifting. For example:

The level of documentation and control for each process is proportionate to its risk to patients, product quality, and compliance.

Once that principle is on record, Management Review can do what a lean system is supposed to do: check what’s relevant, not what merely produces paperwork. Two questions are usually enough to keep the system honest:

A realistic example shows the point. If audits keep finding nothing in a low-risk warehouse process, extend the audit interval, formally, on purpose, and with a short rationale. If complaints start rising in a medium-risk software module, treat that as a signal: lift the process tier, increase testing, and tighten controls where they now earn their keep.

Startups and large corporates need the same risk-based approach. They just enter from different points.

Startups often win by starting small: focus on a tight set of processes (design, purchasing, complaint handling, document control), rate risk there first, and apply one consistent SOP template plus one controls matrix. Consistency beats volume.

Larger corporates often need the opposite move: a “risk rationalisation” project that reviews existing SOPs, tags them by tier, then simplifies or merges low-risk procedures. If an eQMS exists, the risk tag can drive automated workflows—approvals, training assignments, audit planning—so the system enforces proportionality rather than relying on good intentions.

ISO 13485 can feel like a maze, but the standard does not demand maximum paperwork. It demands control where control matters. A lean, risk-based QMS turns that idea into a repeatable method. And that, in practice, is how complexity shrinks, without standards slipping.

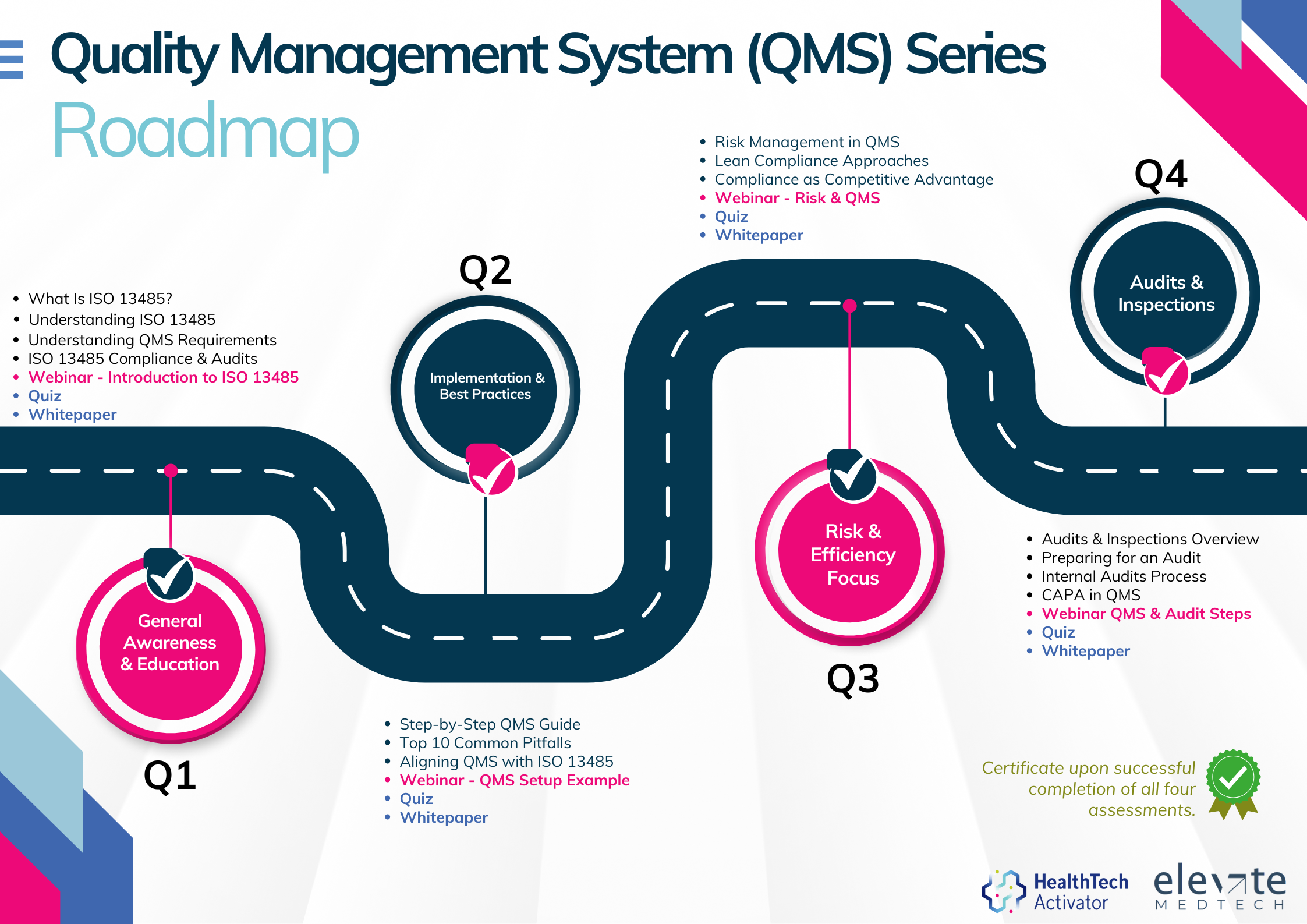

Meeting the requirements of ISO 13485 is one thing, putting them into practice is another. That’s why this article is part of a broader series developed for New Zealand’s HealthTech sector, aimed at helping teams turn regulatory expectations into working systems.

Over 12 months, this series explores ISO 13485 in four parts: from first steps and system setup to risk management and audit readiness. Each quarter combines practical content with interactive workshops to support implementation in real-world settings.

The QMS Series is brought to you by the HealthTech Activator, in partnership with Elevate Medtech.